Introduction

Since mid-2021, in the period preceding the run-up to the South African Municipal Elections that took place on 1 November 2021 to elect councils for district, metropolitan and local municipalities, South Africa experienced a rise of vigilantism against migrants and anti-immigration activism. Vigilantism against migrants and anti-immigration activism existed before 1994 and in the post-apartheid era, and it has often resulted in, or triggered, xenophobic attacks and xenophobic violence. However, it is the emergence of anti-immigration groups that has given rise to some community members, especially in urban areas, conducting vigils aimed at enforcing the country’s immigration laws and labour laws relating to the employment of foreign nationals. The communities are also focused on enforcing compliance with municipal by-laws on the regulation, control and licencing required for hiring and use of municipal premises and facilities for trading by foreign nationals, and the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants (FCD) Act 54 of 1972 together with public health regulations relating to the alleged selling of expired, contaminated, unsafe, unhygienic or counterfeit food and food products by foreign nationals mostly operating spazas or small shops. Anti-immigration groups include Operation ‘Dudula’, the social media-based Put South Africa First Movement, the South Africa First Party, and All Truck Drivers Foundation (ATDF), among others. Vigilantism against migrants in South Africa rose in intensity, scale and scope in the first quarter of 2022, reaching disturbing levels on 7 April 2022, when a Zimbabwean national living in South Africa, Elvis Mbodazwe Banajo Nyathi, was brutally assaulted and burnt to death in the Johannesburg township of Diepsloot.1Times Live (2022) ‘Seven in court accused of vigilante murder of Elvis Nyathi in Diepsloot’,19 April, Available at: <<https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2022-04-19-seven-in-court-accused-of-vigilante-murder-of-elvis-nyathi-in-diepsloot/> [Accessed: 20 April 2022]. As vigilante groups continue to engage in anti-migrant activism and grow their grassroots support and geographical and regional coverage, this paper seeks to interrogate the legality, appropriateness and sustainability of vigilantism against migrants in South Africa. The analysis adds to the ongoing mainstream debate on illegal migration in South Africa.

Photo: GCIS

The State and ‘Crisis’ of Immigration in South Africa

South Africa continues to receive large volumes of migrants in the form of economic migrants, labour migrants, refugees and asylum seekers from neighbouring countries, other African countries, and the rest of the world. The South African government estimates that there may be around 3.95 million migrants living in South Africa as of August 2021.2StatsSA (2021) ‘Erroneous reporting of undocumented migrants in SA’, Media Statement, 5 August, Available at: <https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14569> [Accessed: 4 April 2022]. The influx of migrants – especially labour migrants – into South Africa can be traced back to the opening up of intensive gold mining in the 1880s and later increased in the 1930s during the days of the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA), known commonly known as Wenela. Migrant workers were systematically recruited by WNLA from various Southern African countries to work in the gold mines. With the South African economy performing relatively better than other regional economies, and cycles of conflicts and civil strife in a number of countries in Southern and Eastern Africa, as well as the Horn of Africa, the Great Lakes Region, and West Africa, vast numbers of economic migrants, refugees and asylum seekers continue to flock into South Africa. As early as December 1994, vigilantism against migrants existed in South Africa, as community groups mobilised in campaigns such as Operation Buyelekhaya (go back home) in Alexandra township in Johannesburg.3Ho, Ufrieda (2022) ‘Timeline of hatred and death – xenophobia and South Africa’s record of shame’, Daily Maverick,19 April, Available at: <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-04-19-timeline-of-hatred-and-death-xenophobia-and-south-africas-record-of-shame> [Accessed: 28 April 2022].

Migration theory, migration studies and development literature are awash with varying and often conflicting perspectives on the merits and demerits of migration to host countries and communities. What cannot be disputed is the fact that, in practical terms, migration can be both a curse and a blessing to any host country. Anti-migrant vigilantism has often been accompanied by narratives that portray migrants as a curse rather than a blessing to South Africa.

When the South African Local Government Association (SALGA), the Mayor of Johannesburg, the Mayor of Ekurhuleni, and the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) briefed the Joint Parliamentary Committees of Home Affairs and Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA) on the impact of illegal migration in South African cities in 2019, the City of Ekurhuleni submitted that foreign nationals ‘sold expired, illicit and counterfeit goods’, and engaged in ‘unfair trading competition’ by pegging ‘excessively low prices’, while their trading spaces were not kept clean, which damages the image and brand of the City.4Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2019) ‘Impact of illegal migration on cities: Input from Joburg & Ekurhuleni Mayors, SALGA & Minister’, 22 October, Available at: <https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/29125> [Accessed: 9 April 2022]. It was also noted that illegal migration in the City of Johannesburg ‘compounded serious challenges in the provision of basic services and temporary emergency accommodation (TEA) to residents’.5Ibid. In Ekurhuleni, undocumented migrants were reported to be worsening high youth unemployment, overpopulation and overcrowding, increasing levels of crime, unfair competition for limited municipal opportunities and limited resources, marginalisation of locals, and increased demand for unplanned service delivery, as undocumented migrants use municipal services without proper billing.

Photo: John Hogg/World Bank

The pressure on social services has also been felt in public health facilities, schools and social welfare programmes. In 2013, there were reports that an increasing number of Zimbabwean women were illegally crossing the Zimbabwe-South Africa border to give birth in South African hospitals, as they sought to escape expensive maternity care services and relatively poor neo-natal care services in Zimbabwe.6eNCA (2013) ‘More Zimbabwean women give birth in South Africa’, 8 August, Available at: <https://www.enca.com/south-africa/more-zimbabwean-women-give-birth-south-africa> [Accessed: 10 April 2022]. The South African Minister of Home Affairs shared similar concerns in December 2021, stating that 70% of women giving birth in Musina Hospital in Limpopo Province are from Zimbabwe,7Ncana, Nkululeko (2021) ‘Home Affairs minister will not budge on Zim exemption permits’, City Press,19 December, Available at: <https://www.news24.com/citypress/news/home-affairs-minister-will-not-budge-on-zim-exemption-permits-20211219> [Accessed: 12 April 2022]. which is over-straining South Africa’s health delivery system. In August 2022, the Limpopo Province Member of the Executive Council (MEC) for Health also blatantly expressed her displeasure and exasperation with Zimbabwean migrant patients who sought medical services at hospitals in Limpopo, arguing that this is overburdening the South African health system at a time when 91% of the 5.7 million people in the Province are dependent on the state for medical services.8Karrim, Azarrah (2022) ‘FACT CHECK: No, MEC Ramathuba, poor management is killing Limpopo hospitals – not migrants’, News24,26 August, Available at: <https://www.news24.com/news24/investigations/fact-check-no-mec-ramathuba-poor-management-is-killing-limpopo-hospitals-not-immigrants-20220826-2> [Accessed: 2 June 2023]. The actions and position of the MEC were supported by some anti-migrant vigilante groups and political parties, with the leader of the Patriotic Alliance (PA) maintaining that:

If there is a South African, Zimbabwean and Mozambican patient on oxygen and I see a South African patient born and bred in South Africa, I will turn the oxygen off so that the South African can live.9Times Live (2022) ‘WATCH: Gayton McKenzie would switch off foreigner’s oxygen “to save a South African”’, 30 August, Available at: <https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2022-08-30-watch-gayton-mckenzie-would-switch-off-foreigners-oxygen-to-save-a-south-african> [Accessed: 2 June 2023].

The South African government implemented its COVID-19 Vaccine Roll-Out Programme, which was extended to undocumented foreigners, as per government policy. When the campaign for vaccinations in South Africa was complete, the government spent over R600 million on the estimated 3.95 million migrants alone, if one uses the modest estimates of the Johnson and Johnson Vaccine (single dose), which costs R153 per dose minus the cost of distribution, administration, and other related costs.10Business Tech (2021) ‘South Africa’s Covid-19 vaccine rollout plan: who gets it, what it costs, and how government says it will work’, 7 January, Available at: <https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/459488/south-africas-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-plan-who-gets-it-what-it-costs-and-how-government-says-it-will-work> [Accessed: 12 April 2022]. In terms of educational services, children of undocumented migrants have been receiving basic education at government-subsidised public schools (including access to quintile 1, 2 and 3 schools, which are declared no-fee schools), especially following the landmark ruling made by the Makhanda High Court in the Centre for Child Law vs Minister of Basic Education Case on 12 December 2019.11Southern African Legal Information Institute (2019) Centre for Child Law and Others v Minister of Basic Education and Others (2840/2017) [2019] ZAECGHC 126; [2020] 1 All SA 711 (ECG); 2020 (3) SA 141 (ECG), 12 December, Available at: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAECGHC/2019/126.html> [Accessed: 14 April 2022].

Photo: IMF/James Oatway

The above factors may not sufficiently explain the factors behind the rise of vigilantism against migrants in South Africa. There are factors relating to the existence of other invisible forces; continued power struggles between foreign nationals and host communities; frustration resulting from widening inequality, poverty and competition for scarce resources; challenges of social integration and social cohesion stemming from Apartheid policies of isolationism and exclusion; inadequate public policing that has resulted in violence and impunity in some sections of society; as well as the persistence of sub-cultural and normative factors that propel a culture of violence and hatred of migrants in some communities. All these have collectively become a leitmotif for vigilantism against migrants in South Africa, as they have ignited tensions and hostilities in migrant host communities, resulting in what has been considered a ‘crisis’ of immigration in South Africa.

Photo: Ihsaan Haffejee/GroundUp

The Rise of Vigilantism Against Migrants in South Africa

Vigilantism itself is not a new phenomenon in South Africa and is not unique to this country. It existed well before, during and after the Apartheid era. Mostly it targeted perceived criminals involved in theft, drug peddling, robberies, rape, et cetera. For instance, in the 1980s, anti-apartheid vigilante groups and activists used the infamous ‘necklace method’ against perceived and known apartheid regime collaborators in black townships, wherein they would tie car tyres around the necks of their victims and douse them with petrol in public. In the Western Cape townships of Nyanga, Khayelitsha, Phillipi, Gugulethu, Kraaifontein, and Bishop Lavis, among others, vigilantism continues to increase to date against rising crimes of murder, robbery, public violence, theft, drug peddling, and others. Victims usually succumb to gruesome and brutal mob justice, burning, flogging, sjamboking or stoning. The South African Police Services (SAPS) Crime Statistics First Quarter Report of 2023 stated that there were 588 murders in South Africa caused by vigilantism and mob justice between January and March 2023, with the highest vigilante murders experienced in three provinces, namely Gauteng (164 murders), KwaZulu-Natal (122 murders), and the Eastern Cape (113 murders), while the remainder was spread across the other six provinces.12SAPS (2023) ‘Police Recorded Crime Statistics Republic of South Africa, Fourth Quarter of 2022-2023 Financial year (January 2023 to March 2023)’, p. 18, Available at: <https://www.saps.gov.za/services/downloads/4th-Quarter-January%202023-March%202023.pdf> [Accessed: 2 June 2023].

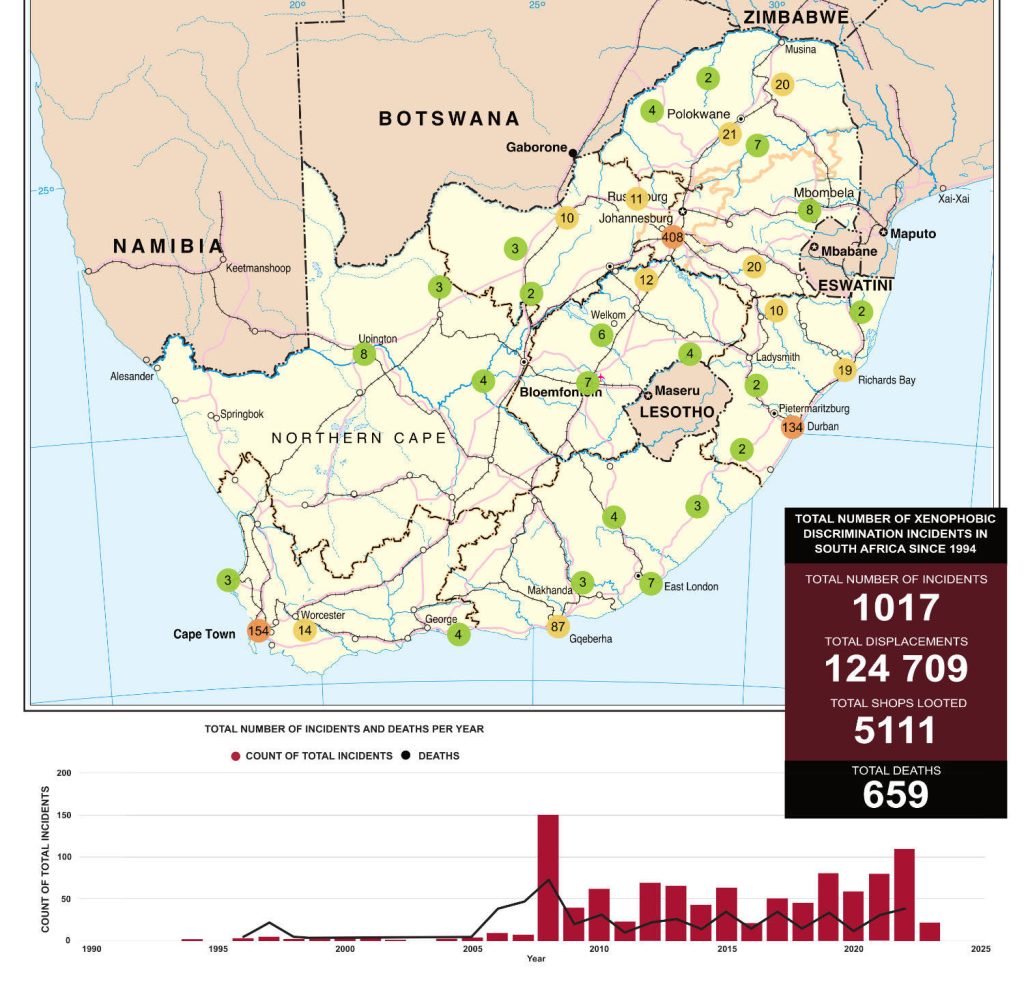

From time to time, several anti-migrant vigilante groups, often loosely organised in migrant-hosting communities, have occasionally targeted undocumented migrants and administered mob justice in acts that have been described as xenophobic violence. The University of the Witwatersrand African Centre for Migration and Society’s (ACMS) Xenowatch reports that from 1994 up to 5 June 2023, South Africa has experienced 1 011 incidents of xenophobia, which have resulted in 659 deaths, the displacement of 124 656 migrants, and looting of 5 111 shops.13ACMS (2023) ‘Xenowatch Dashboard: Incidence of Xenophobic Violence in South Africa: 1994-05 June 2023’, Xenowatch, Available at: <https://www.xenowatch.ac.za/statistics-dashboard> [Accessed: 5 June 2023]. Gauteng, the Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape have the highest number of xenophobic incidents.

The emergence of anti-migrant groups, such as Operation Dudula (in isiZulu, ‘dudula’ means to ‘push back’, ‘push away’, ‘drive out’ or ‘evict’), the social media-based Put South African First Movement, the South Africa First Party, and the ATDF, has exponentially increased tensions in host communities, especially following the killing and burning of Elvis Mbodazwe Banajo Nyathi, a Zimbabwean national living in South Africa, on 7 April 2022. This incident occurred while Operation Dudula was staging protests and visits to business premises and the homes of foreign nationals, ostensibly to search for ‘criminal elements in [South African] communities’. According to the Operation Dudula Movement leadership, ‘it so happens that the majority of the problems in terms of criminality come from illegal foreigners’.14Doyen, Claire (2022) ‘Look: Operation Dudula’s objective is simple – fight criminal elements in our communities’, IOL,29 April, Available at: <https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/look-operation-dudulas-objective-is-simple-fight-against-criminal-elements-in-our-communities-bb2c00ec-5e23-464e-a0b3-3463ac8f4995> [Accessed: 7 May 2022]. The Operation Dudula Movement is also targeting drug dens, unregistered or improperly registered foreign-owned businesses, and undocumented foreigners. The movement gained prominence in June 2021 when it organised operations in Diepkloof, Soweto, advocating for the removal of foreign nationals in South Africa, blaming them for most of the socio-economic challenges faced in the country.15Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2022a) ‘Operation Dudula Movement: SAPS briefing with Ministry’, 1 April, Available at: <https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34710> [Accessed: 8 April 2022]. Operation Dudula has branches in five provinces, namely, Gauteng, the North-West, Western Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo, with plans to launch more in the other provinces.

The ATDF, with support from members of the Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans Association (MKMVA), has also been advocating for 100% employment of South African truck drivers in the freight industry and an end to the continued ‘illegal recruitment practices’ that are benefiting foreigners in the road freight logistics business.16IOL (2020) ‘“100% local truck drivers, or else” warn marchers’, 24 November, Available at: <https://www.iol.co.za/mercury/news/100-local-truck-drivers-or-else-warn-marchers-1ab2ad67-169f-455c-9276-3a2d15592791> [Accessed: 11 April 2022]. Actions by the ATDF resulted in the emergence of civilian groups that interrupt and intercept foreign truck drivers, demanding work permits and proof of their migrant status in South Africa.17Simelane, Bheki C. (2022) ‘“Leave now and leave with something”, trucking group warns foreign drivers’, Daily Maverick, 31 January, Available at: <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-01-31-leave-now-and-leave-with-something-trucking-group-warns-foreign-drivers> [Accessed: 11 April 2022]. Some vigilante groups have confronted employers and companies, giving them ultimatums and demands to halt the recruitment of undocumented foreign nationals. For instance, on 29 March 2022, members of Operation Dudula and Put South Africa First delivered 14-day ultimatums to big companies in Rosslyn industrial area in Akasia, City of Tshwane Municipality (including Afrit Trailers Pty Ltd. and Praga Technical Pty Ltd.), demanding that they stop hiring ‘ghost employees’ and ‘non-documented foreign nationals’.18Tshikalange, Shonisani (2022) ‘Put South Africans first, Operation Dudula tells companies in Tshwane’, Times Live,29 March, Available at: <https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2022-03-29-put-south-africans-first-operation-dudula-tells-companies-in-tshwane> [Accessed: 19 April 2022]. Thus, the rise of vigilantism against migrants has spread hatred, polarisation, disunity, social dissension, and anti-migrant sentiments, which may ultimately ignite xenophobic attacks.

Photo: GCIS

The Legality, Appropriateness and Sustainability of Vigilantism against Migrants in South Africa

In analysing the legality, appropriateness and sustainability of vigilantism against migrants in South Africa, it may be more helpful to define vigilantism in legal terms and dissect the anatomy of vigilantism and vigilante groups. A vigilante generally refers to people that take the law into their own hands by punishing others without any legal authority. Vigilantism refers to such practices. Etymologically, the word is borrowed from the Spanish word vigilante, which means ‘watchman’ or ‘guard’. Black’s Law Dictionary defines vigilantism as ‘the act of a citizen who takes the law into his or her own hands by apprehending and punishing suspected criminals’.19Black’s Law Dictionary (2004) ‘Vigilantism’, 8th edn, p. 4852, Available at: <https://trust.dot.state.wi.us/ftp/dtsd/bts/environment/library/reference/blacks-law-dictionary-8th-edition-(2004).pdf> [Accessed: 5 May 2022]. Thus, vigilantism entails ordinary people taking unofficial actions to investigate and/or catch people believed or perceived to be criminals and then punishing them or enforcing vigilante justice or laws (usually through vigilante patrols or operations in an area) without any legal authority to do so.

According to Chapter 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996), SAPS has the primary responsibility to prevent, combat and investigate crime; uphold and enforce the law; and ensure that criminals are brought to justice. The Local Government Municipal Structures Act 117 of 1998 also empowers the eight metropolitan municipalities of South Africa to maintain their own municipal police units (Metro Police) or specialised units primarily responsible for enforcing municipal by-laws. Therefore, in terms of legal recognition, anti-migrant vigilante groups operate outside the confines and purview of constitutional provisions and law.

The manner in which most vigilante groups administer justice, as was the case with reported cases of undocumented foreign nationals who have been killed, burnt or assaulted, especially during xenophobic attacks, is illegal and inappropriate. Access to justice is a basic human right the world over. Section 34 of the South African Constitution clearly stipulates that everyone has a right to have any dispute that the application of law can resolve decided on in a fair public hearing before a court or independent and impartial tribunal. Even the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) provides that everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal in determining their rights and obligations and any criminal charge against them. Anti-migrant vigilante groups have often killed or assaulted foreign nationals based on accusations of drug peddling from the ‘court’ of public opinion, not on the national justice delivery system. This is an affront to Section 35(3) of the Constitution, which provides that every accused person has a right to a fair trial, and Section 35(3)(h), which states that every person must be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law. In most cases, victims of vigilante justice are at the receiving end of disproportionate punishment.

The claim by anti-migrant vigilante groups is that they are motivated by frustration stemming from the alleged failure by government, specifically SAPS and the DHA, to enforce immigration and criminal laws in the country.20Mncube, Pearl (2022) ‘Operation Dudula: When deep-seated frustration meets prejudice and weak leadership,’ Daily Maverick,20 April, Available at: <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2022-04-20-operation-dudula-when-deep-seated-frustration-meets-prejudice-and-weak-leadership> [Accessed: 5 May 2022]. This may be understandable and also has a moral appeal and resonates with some sections of society who harbour anti-migrant sentiments. However, the ‘popular justice’ or ‘extra-legal justice’ often administered by anti-migrant vigilante groups constitutes a contravention and unjustifiable infringement of the Constitution and rule of law. South African case law has several judgements that have unequivocally and unambiguously condemned vigilante acts, with judges handing down harsh sentences on those convicted. The S vs Mncengi and Others Case involved vigilante killings of suspected criminals in Khayelitsha’s Harare neighbourhood in Cape Town. The matter was brought before the Western Cape High Court in Cape Town on 24 March 2014. The Judge was emphatic and categorical that vigilantism ‘can never be tolerated by the Courts and people should never be allowed, despite circumstances, to take the law in their own hands’.21Southern African Legal Information Institute (2014) S v Mncengi and Others (SS03/2013) [2014] ZAWCHC 214 (24 March 2014). South Africa: Western Cape High Court, Cape Town, Available at: <https://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAWCHC/2014/214.html> [Accessed: 19 April 2022].

Photo: Albert Gonzalez Farran

In terms of procedural fairness and appropriateness of the modus operandi, anti-migrant vigilante groups are culpable and reprehensible. The DHA is mandated to oversee the management and execution of immigration services, and the regulation of admission of persons into, and their departure from, South Africa, in line with the Immigration Act 13 of 2002 and Refugees Act 130 of 1998. Responding to questions from the National Assembly on 29 April 2022, the DHA Minister stated that the DHA Inspectorate conducts regular multi-disciplinary inspections and investigations to detect undocumented persons in South Africa, with SAPS and Metropolitan Police, including inspections of businesses.22Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2022b) ‘Question NW1252 to the Minister of Home Affairs’, 29 April, Available at: <https://pmg.org.za/committee-question/18590> [Accessed: 8 May 2022]. Undocumented foreign nationals are arrested and issued with Orders to Depart or Notices to Report to an Immigration Officer before deportation, while those with criminal allegations against them are brought before the courts of law.23Ibid. On the other hand, the Department of Employment and Labour (DEL) has the responsibility to conduct inspections, compliance monitoring and enforcement of labour laws, including those related to the employment of foreign nationals in South Africa.

The DHA Minister was questioned by delegates on how the government was mitigating victimisation of foreign nationals through the Dudula Campaign in Soweto during the proceedings of the National Council of Provinces (NCOP) of the Northern Cape Legislature on 22 June 2021. His response was:

[T]he operation you are talking about is an illegal operation, if I am not mistaken. It is people taking the law in their own hands and you are aware that when people do that, is a matter that police must deal with. In our case, in home affairs, the only uniform person we have got is an immigration official who will only go to investigate immigration transgressions… On the other hand, in operations like ‘Operation O Kae Molau’ when police go out to look for criminals… the immigration officials join them.24Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2021) ‘Hansard: NCOP: Unrevised hansard’, National Council of Provinces Meeting, 22 June, Available at: <https://pmg.org.za/hansard/33289> [Accessed: 18 April 2022].

Even the President of South Africa has expressed condemnation of anti-migrant vigilante groups in his public disapproval and admonishment of Operation Dudula, equating Operation Dudula’s vigilante methods (of demanding identification documents of persons to detect undocumented migrants) as synonymous with the segregatory Apartheid-era Pass Laws,25Business Tech (2022) ‘Ramaphosa sends security warning to South Africa’, 11 April, Available at: <https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/575938/ramaphosa-sends-security-warning-to-south-africa> [Accessed: 28 April 2022]. which restricted the mobility of black South Africans and forced them to carry passbooks, popularly known as a dompas. Therefore, the informal and surrogate policing activities of anti-migrant vigilante groups are outside the prescripts and precincts of the law.

Photo: Discott

Recommendations: Addressing the Structural Causes and Drivers of Vigilantism against Migrants in South Africa

Given their illegality and inappropriate modus operandi, it is difficult to fathom the sustainability of vigilantism against migrants in any democratic state. However, it may not be surprising that anti-migrant vigilante groups continue to operate and new ones proliferate based on four main factors. These factors are the basis of the recommendations of this paper.

Firstly, by nature, anti-migrant vigilante groups are not registered entities. Rather, they are social movements that are difficult to regulate. The Minister of Police, Bheki Cele, responding to the question on why they have not banned operations such as Dudula, stated, without prevarication, that SAPS ‘could not stop organizations [such as Operation Dudula], but could arrest individual criminals’, adding that ‘the police had no right to determine which organizations should exist or not’.26Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2022a), op. cit. The Government of South Africa has to take a firm and decisive position on vigilantism, with due consideration to its effects and implications on creating peaceful, cohesive and stable societies governed by the principles of democracy, freedom, human rights and the rule of law.

Secondly, if the root causes and genuine grievances behind the emergence of anti-migrant vigilante groups are not addressed – that is, rising poverty, increasing competition for shrinking job opportunities, widening inequality, deteriorating social service delivery, and the failure of municipal authorities to cope with the effects of urbanisation – vigilantism against migrants may continue to rise and even intensify. The Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) Quarterly Labour Force Survey reported in May 2023 that the official unemployment rate in South Africa for the first quarter of 2023 stood at 32.9%, the number of unemployed persons increased by 179 000 to 7.9 million in the same quarter, and 4.9% of employed persons were in time-related underemployment.27StatsSA (2023) ‘Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) – Q1: 2023’, Media Release, 16 May, p. 1, Available at: <https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Media%20release%20QLFS%20Q1%202023.pdf> [Accessed: 2 June 2023]. The International Monetary Fund projects the unemployment rate to reach 34.8% by 2025.28International Monetary Fund (2023) ‘South Africa: Country Data’, 2 June, Available at: <https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/ZAF> [Accessed: 2 June 2023]. With respect to inequality, South Africa remains the most unequal country in the world.29World Bank (2022) ‘New World Bank Report Assesses Sources of Inequality in Five Countries in Southern Africa’, Press Release, 9 March, Available at: <https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/03/09/new-world-bank-report-assesses-sources-of-inequality-in-five-countries-in-southern-africa> [Accessed: 5 May 2022]. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report for 2023 identifies five key risks that confront South Africa over the next decade, namely, state collapse, debt crises, collapse of services and public infrastructure, cost-of-living crises, and employment and livelihood crises.30World Economic Forum (2023) ‘Global Risks Report for 2023’, Insight Report,18th edn, p. 88, Available at: <https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-report-2023> [Accessed: 2 June 2023]. If more energy and resources are deployed towards implementing the country’s post-COVID-19 Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan (ERRP) and the National Development Plan’s (NDP) vision to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by 2030, most of the socio-economic challenges giving rise to vigilantism will be addressed.

Photo: GCIS

Thirdly, if public confidence in the public policing functions and criminal justice delivery system (or public perception on the same) continues to diminish, anti-migrant vigilantism may continue to rise. In light of this, SAPS and other law enforcement agencies, the DHA and the newly established Border Management Authority (BMA) have to address identified limitations in preventing illicit and unauthorised movement across the country’s borders. Reported corruption at ports of entry, ineffective implementation of migration laws, labour laws and municipal by-laws, and ineffective inspection of businesses by labour officials and public health regulators may need attention.

Fourthly, if complementary efforts are not comprehensively funded and executed, the belief that ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it’ (espoused in the National Constitution and Freedom Charter of June 1955) may turn out to be an elusive and distant dream. Without such efforts directed at pursuing the strategic objectives of social cohesion and nation-building – as reflected in the Constitution, NDP 2030, National Strategy for Developing an Inclusive and Cohesive South African Society of 2012, and the Social Cohesion and Nation Building Compact – South Africa ‘will never be prosperous or free until all our people live in brotherhood’. The government and other community-based grassroots organisations across all provinces need to work closely with the government-established Inter-Ministerial Committees on Migration, Social Cohesion, Population Policy, and the Employment of Foreign Nationals to address underlying issues behind the rise of anti-migrant vigilantism and to implement initiatives that promote peaceful co-existence, social integration, and unity in diversity. At the same time, vigilante crimes may also need to attract more deterrent and preventative actions and corrective sentences.

Photo: GCIS

Conclusion

As demonstrated in the analysis, vigilantism against migrants continues to gain momentum in terms of the intensity of activities and geographical spread. However, they remain illegal and their modus operandi is inappropriate, as they are in contravention of the Constitution, natural justice principles, and basic human rights of affected people. The rise of vigilantism against migrants poses a serious threat to the safety and security of foreign nationals and host communities, as it ignites hostilities, tensions, hatred, lawlessness, and anarchy in South African communities, which all trigger xenophobia. The South African government may need to engage anti-migration vigilante groups progressively and collectively to identify their grievances, the underlying factors behind anti-migrant vigilantism, and the proximate, distal and immediate causes of vigilantism against migrants to find durable and comprehensive solutions to address these problems.

Dr Clayton Hazvinei Vhumbunu is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations and Governance in the Department of Political Studies and Governance at the University of the Free State (UFS) in Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Charity Mawire is a PhD candidate in Migration and Displacement and a Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) Scholar based at the African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.