Introduction

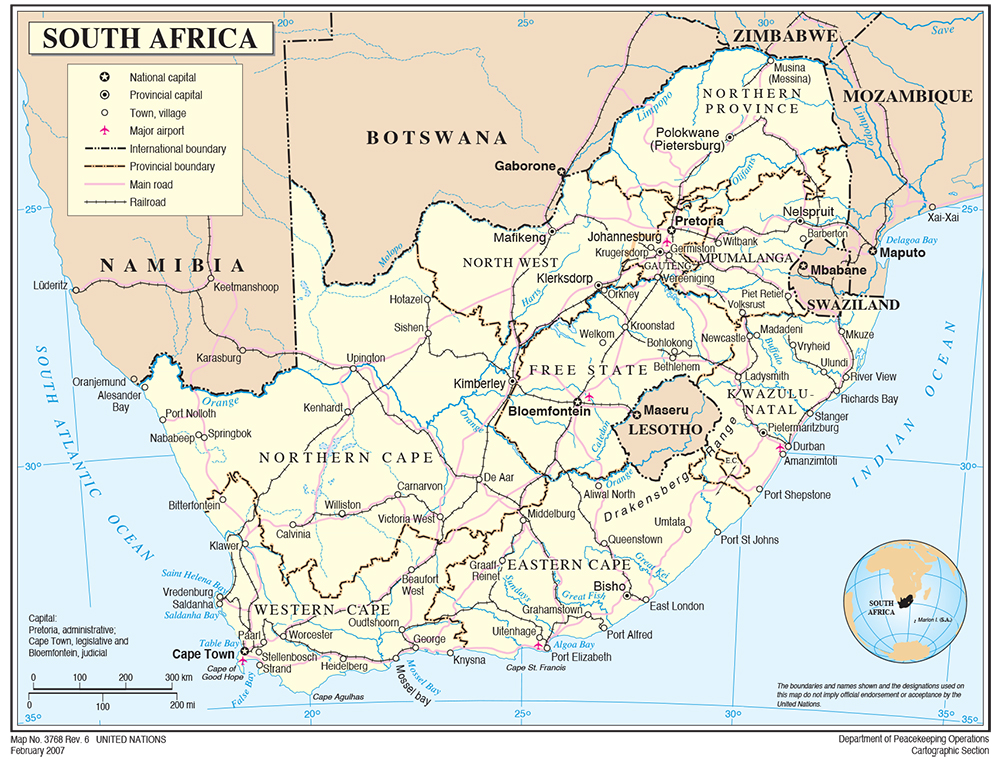

During the period 9 to 17 July 2021, South Africa experienced violent protests and socio-political unrest characterised by widespread looting of shops and businesses, as well as burning and destruction of public facilities and private properties, mostly in the provinces of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and Gauteng. The socio-political unrest and violence were largely sparked by initial low-intensity and sporadic protests in parts of KZN against the arrest and imprisonment of former President Jacob Zuma. The Constitutional Court of South Africa sentenced the former president to 15 months imprisonment for defying its order to comply with the summons to appear before the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State, and for undermining the authority of the Court through his casual and scandalous attacks. There has been wide-ranging debate across the country on whether the ‘Free Zuma’ protests, looting and socio-political unrest was caused by the imprisonment of Zuma or not. However, what stands out is not only the undeniable fact that the developments resulted in colossal socio-economic damage countrywide at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic is wreaking havoc on national economic growth and people’s lives and livelihoods, but also the valuable lessons for sustainable future prevention, management and resolution of conflict, violence and socio-political unrest in South Africa. This article deepens the analysis into the causes and consequences of the Free Zuma socio-political unrest while reflecting on the possible valuable lessons that can be drawn from the events to avoid the recurrence of such and to manage and resolve similar conflicts in the future sustainably.

Background to the ‘Free Zuma’ Protests and Socio-Political Unrest in South Africa

Political and social tensions, mostly in KZN province and, started to intensify when the former president started appearing before the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State between 15 and 19 July 2019 to provide evidence and testimony on allegations of corruption and state capture-related issues. The Commission was established in January 2018 by the then-President Jacob Zuma, with Deputy-Chief Justice Raymond Zondo appointed by the Chief Justice as the Chairperson, in accordance with Section 84(2) of the Constitution, pursuant to investigation and remedial action of the Public Protector with regards to complaints and allegations of State Capture.[1] Initially, Zuma made a court application to interdict the Public Protector Report on State Capture, but the North Gauteng High Court ruled on 14 December 2017 that the remedial actions of the State Capture Report were ‘wise, necessary, rational and appropriate’.[2]

In December 2020, the Chairperson of the Commission summoned Zuma to reappear before the Commission to respond to ‘critical questions’ on ‘various issues arising out of evidence given by various witnesses’, specifically his role ‘in regards to various transactions and matters’.[3] Zuma was summoned to appear before the Commission between 18 and 22 January 2021, but continuously expressed reluctance to appear before the Commission, citing his treatment as an accused rather than as a witness, health concerns, and later he unsuccessfully appealed for the recusal of the Chairperson of the Commission. Even after the Constitutional Court passed a judgement on 28 January 2021 that compelled him to appear before the Commission between 15 and 19 February 2021, Zuma continued to be defiant, stating that he was prepared to be arrested and incarcerated.[4]

The Commission launched contempt of court proceedings at the Constitutional Court. On 29 June 2021, the Constitutional Court sentenced Zuma to 15 months in prison on the grounds that by failing to comply with the court order to testify before the Commission, his conduct constituted a ‘reprehensible attack on the rule of law’ and his contempt of court ‘posed a serious risk that it would inspire others to undermine the administration of justice’.[5] In its judgement, the Court ordered Zuma to submit himself to the South African Police Service (SAPS) in Nkandla or at Johannesburg Central Police Station within five days, failure of which would result in his arrest.[6] Protesters gathered at Zuma’s homestead in Nkandla to protect him from being arrested. His two court appeals at the Pietermaritzburg High Court and at the Constitutional Court to stay the execution of his arrest were unsuccessful. When Zuma handed himself over at Estcourt Correctional Service Centre in KZN on 7 July 2021, there were widespread violent protests, rioting and looting of shops and businesses, and destruction of public facilities and private property in parts of KZN. This spread to parts of Gauteng province from 9 to 17 July 2021. The ‘Free Zuma’ protests resulted in extensive damage to the economy and businesses, while threatening the lives and livelihoods of the people who were already reeling under the effects of Covid-19.

Quantifying the Socio-economic Losses and Consequences of the Riots and Destruction

While assessments to determine the extent of the damage that occurred during the nine days of protest and unrest are ongoing, it is clear that the effects have been tremendous in both scale and intensity. The protests resulted in the loss of properties, business stock, employment, livelihoods, and essential services, such as medical and pharmaceutical supplies (in hospitals and clinics), farming, financial services facilities, telecommunication facilities, food distribution centres, and seaports. The protests also disrupted critical government programmes, such as the Covid-19 vaccination programme. Hence it has been considered unprecedented and ‘the worst unrest since Apartheid’.[7]

By disrupting businesses through looting and arson and damaging business premises and properties, the protests caused significant financial and infrastructural losses. The South African Property Owners’ Association (SAPOA) reported that a total of 3 000 stores were looted, and 1 199 retail stores were damaged during the protests, including large outlets and businesses.[8] A total of 161 malls were damaged countrywide, while 161 liquor outlets and distributors, 11 warehouses, and eight factories were extensively damaged.[9] Banking services were affected, as most banks in KZN and Gauteng closed their branches.[10] In total, an estimated 40 000 businesses and 50 000 informal traders were affected, with 150 000 jobs put at risk, mostly due to business closures and the possibilities of delayed re-stocking and re-opening.[11]

On a national scale, SAPOA estimated that the extent of damage was worth R50 billion. The KZN province lost R20 billion, and in Durban alone, R1.5 billion of stock was lost by businesses.[12] Large supermarket groups and wholesalers were mainly targeted and affected. For example, Shoprite Group Stores reported that out of its 1 189 supermarkets trading under different names, a total of 200 Shoprite Group Stores were looted, vandalised and/or burnt in KZN and Gauteng, including 69 Shoprite supermarkets, 54 Shoprite Liquor Shop outlets, 44 Usave stores, 35 furniture stores, six Checkers supermarkets, one Checkers Hyper, and one Freshmark Distribution Centre.[13] Massmart Holdings Limited reported that 41 of its stores had been looted in KZN and Gauteng, with four facilities burnt and damaged.[14] All this consequently led to food shortages and under-supply of basic commodities in the affected provinces.

The protesters blockaded and damaged parts of the main national highways, thereby disrupting commercial traffic along the routes which serve as strategic logistics arteries nationally and regionally. More than 35 trucks were burnt and looted, mostly at Mooi River Town in KZN. The 2 255km national (N2) highway connects Cape Town with Durban, while the 579km national (N3) highway connects Gauteng with KZN. The latter is a strategic route in Southern Africa along the North-South corridor as it facilitates road transit freight and commercial cargo traffic from landlocked countries, such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, carrying imports and exports to and from the strategic seaports of Durban (which is Africa’s busiest port) and Richards Bay as well as King Shaka International Airport. Over and above this supply chain disruption, essential services were suspended. This included the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA), which delivers commuter metro-rail train services in metropolitan areas, and the South African Petroleum Refineries (SAPREF) oil refinery, which suspended services citing force majeure.[15] SAPREF is the largest refinery in Southern Africa, accounting for 35% of South Africa’s fuel supply. EThekwini Municipality suspended its municipal bus services and its electricity call centre,[16] while the electricity utility (Eskom) suspended its service calls in parts of KZN and Gauteng.[17] Telecommunications infrastructure was destroyed, with the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) reporting that 113 networks had been vandalised, which disrupted network services and community radio stations.[18] In addition, there was looting and destruction of radio stations and community radio equipment,[19] which infringed on citizens’ rights to access information, entertainment and news.

The violent protests impacted the Covid-19 vaccination roll-out and disrupted the transportation of medical supplies and delivery of healthcare services.[20] The South African Department of Health reported that about 25 000 vaccine doses were lost during protest action through acts of looting and arson. The target of vaccinating 300 000 people per day was impeded[21] at a time when the government sought to vaccinate 67% of the population by the end of 2021 to reach herd immunity. The closure of over 90 pharmacies in KZN and Gauteng affected the collection of essential medicines by people living with chronic illnesses.[22]

Communal violence and racial tensions were sparked as a result of vigilantism. Business owners and armed civilians resorted to self-defence, self-protection, and community citizen policing. In the Phoenix community in Durban, the official death toll reached 36 people, with allegations of racial profiling and ‘race-targeted’ attacks on suspected looters and pillagers.[23] Overall, the July 2021 protests resulted in the deaths of 337 people in KZN and Gauteng as of 22 July 2021, with over 3 400 people arrested on allegations of inciting public violence, murder, arson, and looting.[24]

The protests impacted farming, mining, and manufacturing in the two provinces. For example, Tongaat Hulett sugar cane plantations in KZN were burnt, resulting in losses of approximately 300 000 tons.[25] Trucks transporting cane to the sugar mills for processing were hijacked, resulting in the closure of the mills.[26] Coalmining in KZN was disrupted due to protest-induced absenteeism among workers.[27] This affected the productivity of mining firms, with companies like MC Mining Uitkomst colliery announcing that the three and half days of temporary closure resulted in 5 600 tons of forfeited coal production, which translated into export losses.[28] There could be long-term economic implications, which may affect investment decisions. For example, companies such as Toyota, which has a car manufacturing plant in KZN, have raised serious concerns about the conduciveness of the province’s business environment.[29]

Significant costs were incurred by business owners in the repair and rehabilitation of buildings and the re-stocking of shelves. For example, Montclair Mall in Durban will cost between R30 and R50 million to repair.[30] The South African Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, in conjunction with the Industrial Development Corporation and the National Empowerment Fund, commendably announced a R3.75 billion funding package as part of the ‘economic recovery support interventions’ to assist businesses, including small and informal enterprises in townships, rural areas and small towns affected by the protests, as well as an additional R400 million under the Manufacturing Competitiveness Enhancement Programme Economic Stabilisation Fund to support affected manufacturing firms.[31] However, this remains insufficient considering the significant losses incurred by businesses.

Causes of the July 2021 Protests and Socio-political Unrest

There has been fierce debate in academia, political circles, and public spaces on the real causes of the July 2021 protests and socio-political unrest. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, in his address on 16 July 2021, described the protests as ‘nothing less than a deliberate, coordinated, and well-planned attack on [South Africa’s] democracy’, and further stated that ‘the Constitutional order of [South Africa’s] democracy was under threat’.[32] The president declared:

The actions are intended to cripple the economy, cause social stability and severely weaken – or even dislodge – the democratic state. Using pretext of a political grievance, those behind these acts have sought to provoke a popular insurrection. They sought to exploit the social and economic conditions under which many South Africans live […] to provoke ordinary citizens and criminal networks to engage in opportunistic acts of looting. The ensuing chaos is used as a smokescreen to carry out economic sabotage.[33]

The president’s sentiments that the protests and civil unrest were ‘an attempted coup’ and ‘insurrection’ may be validated once the ongoing investigations to identify the architects and instigators of the ‘economic sabotage’ and ‘attempted regime change’ by the Crime Intelligence Division of the SAPS and the State Security Agency (SSA) is completed. While the involvement of a ‘third force’ may be a possibility, it is the continued existence of enabling factors for social unrest that contributed significantly to the situation that unfolded.

The enabling factors, which may qualify as the root causes of the July 2021 protests and looting, centre around challenges faced by the state to address the problems of poverty, unemployment, and inequality as these often create portions of communities that are economically disenfranchised, desperate and marginalised. Therefore, they identify common grievances and shared bonds as they engage in survivalist-motivated violence and frustration-instigated social unrest or are prone to manipulation by elites to fight political battles on their behalf. The World Bank ranks South Africa as the most unequal society in the world, with 90% of the country’s wealth being owned by only 10% of the population.[34] The United Nations Human Development Report of 2020 reports that 55.5% of South Africans (approximately 30.3 million) are living below the poverty line.[35] Job losses have increased since the onset of Covid-19. The Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) of 2021 puts unemployment in South Africa at 32.5%, and even higher at 46.3% among young people (15 to 34 years of age), while the graduate unemployment rate for those between 15 to 24 years of age stands at 40.3%.[36] In the first quarter of 2021, total employment in the formal non-agriculture sector was reduced by 5.4% compared to March 2020 levels, equating to 552 000 job losses.[37] The government must be commended for introducing a raft of social safety net interventions and social protection measures to cushion citizens from the socio-economic effects of Covid-19, such as the South African Social Security Agency Relief grants and Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grants and food parcels; adjusting pensions for the elderly and grants for child support, foster children, war veterans, and those with disabilities; and the use of the Unemployment Insurance Fund, among others. However, they have had limited reach. A substantial section of society remains in socio-economic distress.

Citizens were frustrated by worsening poverty, unemployment, food insecurity, and inequality due to the Covid-19-induced national lockdown measures. South Africa remains the hardest hit by the pandemic on the continent, with a total of 2 919 632 cumulative confirmed cases and 88 925 cumulative deaths as of 25 October 2021.[38] Exacerbated by the pandemic and falling living standards, life expectancy for males has declined from 62.4 years in 2020 to 59.3 years in 2021 and for females from 68.4 years in 2020 to 64.6 years in 2021.[39] Economic growth has been very minimal, with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth of a mere 1.1% in the first quarter of 2021, making the economy 2.7% smaller than it was in the first quarter of 2020.[40] Therefore, although the July 2021 protests may have been politically motivated, they were fueled by deep-rooted and acute socio-economic challenges facing poor, hungry and frustrated citizens, mostly in the townships, which provided fertile ground for social unrest.

Key Lessons in Preventing, Managing, and Resolving Future Socio-political Unrest in South Africa

The government finally managed to restore calm following the deployment of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) to KZN and Gauteng between 12 and 14 July 2021, as part of ‘Operation Prosper’ in response to a request made by the National Joint Operational and Intelligence Structure (NATJOINTS). There are key lessons that emerge from the July 2021 protests that the government, businesses, communities and society must consider for future prevention, management, and resolution of such socio-political unrest.

First, it is incumbent upon the government to invest in strategically readjusting its socio-economic policies to allow for transformational, inclusive and equitable economic growth that benefits the poor and vulnerable in society, instead of perpetuating the legacy of exclusion and entrenching inequality. Existing national plans, programmes and policies have to be implemented in such a way that facilitates the equitable distribution and redistribution of socio-economic development benefits to all members of the society. Prudent and strategic economic policies have to be complemented by social welfare, social security and social protection programmes that cater for the vulnerable members of society in order to create peaceful communities. This addresses some of the root causes of unrest and discontent, as it becomes difficult for any criminal elements to manipulate, incite or negatively influence empowered citizens.

To reinforce the previous point, the government is encouraged to invest in civic infrastructure and community engagement to foster community development and promote social cohesion. A culture of looting, violence, and arson continues to characterise protests, as witnessed during the waves of service delivery protests and xenophobia in recent years. South Africa is currently ranked among the 35 most dangerous countries in the world on the Global Peace Index of 2021 in terms of safety and security considerations.[41] A lesson that can be drawn from the July 2021 protests is the need for strict enforcement of laws against pillaging, arson, and destruction of property through effective sentencing of convicts and upholding the rule of law. As envisaged in the National Crime Prevention Strategy of South Africa, the government may need to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the criminal justice system such that reported crimes are expeditiously and successfully investigated and prosecuted, and convicts receive punishment for serious crimes committed. This will deter similar future cases of criminality and violence. It should be coupled with enhanced police-community relations to nurture a culture that shuns violence and criminality as well as public attitudes, norms, and beliefs geared towards peaceful co-existence of those with similarities and differences in society. In the process, community members may also need to develop a culture of safeguarding public facilities and shared public spaces from vandals, criminals and pillagers. All this is achievable through structured, massive civic education that targets children, young people and adults to promote the values of civility, peace, responsible citizenship, collective sense of identity and belonging, respect for the sanctity of life and property, and good neighbourliness.

Another lesson that emerged from the protests is the salience of community race relations. Other than implementing nation-building and social cohesion programmes, as provided for in the National Strategy for Social Cohesion of 2012, the SAPS may need to execute civilian police programmes effectively to ensure that community policing and neighbourhood watch programmes are conducted by trained, competent and professional individuals who are in a position to manage and resolve conflicts without provoking community tensions, as opposed to the illegal practice of setting up community checkpoints and aggressive vigilantism.

Proactive policing is needed as a preventive measure to manage violence and unrest. There were reports that firearms, ammunition, and assault rifles were looted during the protests in Johannesburg.[42] This may have been avoided if timeous proactive measures were taken. The government should continuously enhance the capacity and competencies of the security services sector by improving their ability to understand, assess and analyse trends and patterns in conflict, violence and instability so as to be able to intervene systematically, strategically and tactically for public safety. In addition, exemplary leadership is recommended, especially at the political leadership level, through nurturing productive and constructive political relationships, political tolerance, and ethical conduct such that political leaders can maintain a moral high ground when they condemn incidences of violence, looting, impunity and anarchy.

Conclusion

The cause of the July 2021 socio-political unrest was a combination of political, social and economic factors. While the protests and unrest left deep wounds on the country’s political, economic, social and legal system, it also presents an opportunity for the country to draw on lessons that are essential for future prevention and management of various forms of conflict and violence. As Kenneth Cloke and Joan Goldsmith once remarked:

Every conflict we face is rich with positive and negative potential; it can be a source of inspiration, enlightenment, learning, transformation and growth, rage, fear, shame, entrapment, and resistance. The choice is not up to our opponents, but to us, and our willingness to face and work through them.[43]

What then remains fundamental is the ability of the South African government, communities and businesses to reflect on the lessons learnt retrospectively and collectively make efforts to prevent the recurrence of similar situations. This will better position South Africa to manage and resolve future conflicts sustainably, peacefully and in a manner that limits the severity, intensity and scale of socio-economic and political damage.

Dr Clayton Hazvinei Vhumbunu is a Senior Programme Coordinator at the National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS) in Johannesburg, South Africa. The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone; they do not represent the position and opinions of NIHSS or its staff.

End Notes

[1] Republic of South Africa (2016) ‘Report on the Investigation into Alleged Improper and Unethical Conduct by the President and Other State Functionaries relating to Alleged Improper Relationships and Involvement of the Gupta Family in the Removal and Appointment of Ministers and Directors of State-Owned Enterprises Resulting in Improper and Possibly Corrupt Award of State Contracts and Benefits to the Gupta Family’s Businesses’, Report No. 6 of 2016/17, 14 October, p. 353, Available at: http://www.saflii.org/images/329756472-State-of-Capture.pdf [Accessed 26 July 2021]

[2] Tandwa, Lizeka (2017) ‘Scathing Judgement Finds Madonsela’s Actions against Zuma Wise, Necessary, Rational, Appropriate’, News24, 13 December, Available at: https://www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/News/scathing-judgment-finds-madonselas-actions-against-zuma-wise-necessary-rational-appropriate-20171213 [Accessed 27 July 2021].

[3] eNCA (2020) ‘Zuma Needs to Answer Allegations: Zondo’, 21 December, Available at: https://www.enca.com/news/zuma-needs-answer-allegations-zondo [Accessed 24 July 2021].

[4] Morais, Sheldon (2021) ‘State Capture Inquiry: Zuma Won’t Appear before Zondo Commission, Lawyer Confirms’, News24, 15 February, Available at: https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/just-in-state-capture-inquiry-zuma-wont-appear-before-zondo-commission-lawyer-confirms-20210215 [Accessed 29 July 2021].

[5] Constitutional Court of South Africa (2021) ‘Secretary of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegation of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in The Public Sector Including Organ Of State V Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma: CCT52/21 [2021] ZACC 18’, Post-Judgement Media Summary, 29 June, Available at: https://www.concourt.org.za/index.php/judgement/398-secretary-of-the-judicial-commission-of-inquiry-into-allegation-of-state-capture-corruption-and-fraud-in-the-public-sector-including-organ-of-state-v-jacob-gedleyihlekisa-zuma-cct52-21 [Accessed 31 July 2021].

[6] Constitutional Court of South Africa (2021) ‘Secretary of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State v Zuma and Others [2021] ZACC 18’, 19 June, p. 2, Available at: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2021/18.pdf [Accessed 2 August 2021].

[7] Cotterill, Joseph (2021) ‘South Africa Counts the Cost of its Worst Unrest Since Apartheid’, Financial Times, 25 July, Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/1b0badcd-2f81-42c8-ae09-796475540ccc [Accessed 3 August 2021]; Winning, Alexander and Roelf, Wendell (2021) ‘Worst Violence in Years Spreads in South Africa as Grievances Boil Over’, Reuters, 13 July, Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/looting-violence-grips-south-africa-after-zuma-court-hearing-2021-07-13 [Accessed 3 August 2021].

[8] The large businesses and outlets include Cashbuild (South Africa), Edgars Stores, PEP Stores, Shoprite, SPAR, Mr Price Group, Massmart Holdings, Woolworths Holdings, KFC, Checkers and Checkers Hyper Supermarkets, OK Stores, Makro Stores, Game Stores, and Cambridge Food Stores, among many others. See Warby, Vivian (2021) ‘About 800 Stores Looted, 100 Malls Damaged and Over R20bn Lost – Sapoa’, IOL News, 19 July, Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/about-800-stores-looted-100-malls-damaged-and-over-r20bn-lost-sapoa-c549f3f1-5d21-44cb-b995-4891ff4644f3 [Accessed 4 August 2021].

[9] Dludla, Ngobile (2021) ‘South Africa Property, Retail Firms Bet on Townships Despite Unrest’, Reuters, 29 July, Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/south-africa-property-retail-firms-bet-townships-despite-unrest-2021-07-29 [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[10] For example, Capitec Bank closed 300 branches and Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), Nedbank closed 226 branches, and ABSA Bank and Standard Bank closed 375 branches and 197 branches respectively in KZN and Gauteng. See Mchunu, Sandile (2021) ‘SA’s Banks Close Hundreds of Branches to Limit Destruction’, IOL News, 15 July, Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/companies/sas-banks-close-hundreds-of-branches-to-limit-destruction-8c8ba764-c83c-4b2a-865b-95c28b556d86 [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Naidoo, Suren (2021) ‘Over 200 Shoprite Group Stores Looted in Last Week’s Unrest’, Moneyweb, 20 July, Available at: https://www.moneyweb.co.za/news/companies-and-deals/over-200-shoprite-group-stores-looted-in-last-weeks-unrest [Accessed 4 August 2021].

[14] Child, Katharine (2021) ‘Massmart had 41 Stores Looted, 4 Facilities Damaged Due to Arson’, Business Live, 16 July, Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/companies/retail-and-consumer/2021-07-16-massmart-had-41-stores-looted-4-facilities-damaged-due-to-arson [Accessed 6 August 2021]; see also SA News (2021) ‘Thousands of Jobs at Risk as Government Consolidates Relief Proposals’, 20 July, Available at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/thousands-jobs-risk-government-consolidates-relief-proposals [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[15] Steyn, Lisa (2021) ‘Fuel Refinery Sapref Declares Force Majeure and Shuts Plant Amid Unrest’, Business Live, 13 July, Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2021-07-13-fuel-refinery-sapref-declares-force-majeure-and-shuts-plant-amid-unrest [Accessed 7 August 2021]; see also SABC News (2021) ‘Multiple Transport Services Suspended in KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng Due to Ongoing Unrest’, 12 July, Available at: https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/multiple-transport-services-suspended-in-kwazulu-natal-gauteng-due-to-ongoing-unrest [Accessed 7 August 2021].

[16] Naidoo, Jehran (2021) ‘eThekwini Residents Stranded as Service Delivery Shuts Down Amid Violent Protests’, IOL News, 12 July, Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/ethekwini-residents-stranded-as-service-delivery-shuts-down-amid-violent-protests-ca2c9395-6751-5784-ac15-903f255c8d34 [Accessed 7 August 2021].

[17] IOL News (2021) ‘Eskom Suspends Service Calls in KZN, Joburg Areas Affected by Protests’, 12 July 2021, Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/eskom-suspends-service-calls-in-kzn-joburg-areas-affected-by-protests-6264e5de-5f82-466f-9cc2-d0264fa15b88 [Accessed 7 August 2021].

[18] ICASA (2021) ‘ICASA Urges Communities to Safeguard the Communication Infrastructure against Vandalism’, 13 July, Available at: https://www.icasa.org.za/news/2021/icasa-urges-communities-to-safeguard-the-communication-infrastructure-against-vandalism [Accessed 4 August 2021].

[19] Some of the radio stations and community radios whose equipment were looted and destroyed include Alex FM, Mams FM, and Westside FM in Gauteng as well as Ntokozo FM in Pinetown, Durban. See Sonjica, Nomahlubi (2021) ‘More than 100 Network Towers Hit in Violent Protests: Icasa’, Sowetan Live, 14 July, Available at: https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2021-07-14-more-than-100-network-towers-hit-in-violent-protests-icasa [Accessed 4 August 2021].

[20] South African Department of Health (2021) ‘Impact of Violent Protests on Health Services’, Media Statement, 13 July, Available at: https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/07/13/media-release-impact-of-violent-protests-on-health-services [Accessed 8 August 2021].

[21] Business Tech (2021) ‘South Africa has a New Covid-19 Vaccine Target for Christmas’, 22 July, Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/trending/508010/south-africa-has-a-new-covid-19-vaccine-target-for-christmas [Accessed 8 August 2021].

[22] Malan, Mia (2021) ‘Half of KZN Patients have no Chronic Medication. Here’s How Looting Affected SA’s Covid-19 Vaccine Roll-out’, Mail & Guardian, 16 July, Available at: https://mg.co.za/health/2021-07-16-half-of-kzn-patients-have-no-chronic-medication-heres-how-looting-affected-sas-covid-19-vaccine-roll-out [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[23] Times Live (2021) ‘Criminal and Dangerous: Ramaphosa Condemns Phoenix “Vigilantism”’, 26 July, Available at: https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2021-07-26-criminal-and-dangerous-ramaphosa-condemns-phoenix-vigilantism [Accessed 8 August 2021].

[24] SA News (2021) ‘Unrest Death Toll Rises to 337’, 22 July, Available at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/unrest-death-toll-rises-337 [Accessed 7 August 2021].

[25] Kruger, Adriaan (2021) ‘Cane Fields Burnt in KwaZulu-Natal, Sugar Mills Shut’, The Citizen, 15 July, Available at: https://citizen.co.za/business/2570804/cane-fields-burnt-in-kwazulu-natal-sugar-mills-shut [Accessed 9 August 2021].

[26] Poonusamy, Purnal (2021) ‘Tongaat Hullet Sugar Mills Shut during Unrest’, The Witness, 13 July, Available at: https://www.news24.com/witness/News/KZN/tongaat-hullet-sugar-mills-shut-during-unrest-20210713 [Accessed 9 August 2021].

[27] Mining MX (2021) ‘Coal Production from KwaZulu-Natal Disrupted by Last Week’s Violent Protests’, 19 July, Available at: https://www.miningmx.com/news/energy/46820-coal-production-from-kwazulu-natal-disrupted-by-last-weeks-violent-protests [Accessed 9 August 2021].

[28] Steyn, Lisa (2021) ‘MC Mining’s KwaZulu-Natal Operations Resume’, Business Live, 19 July, Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/companies/mining/2021-07-19-mc-minings-kwazulu-natal-operations-resume [Accessed 9 August 2021].

[29] Maromo, Jonisayi (2021) ‘Toyota Raises Red Flags Over its KZN Business Following Riots’, IOL News, 19 July, Available at: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/toyota-raises-red-flags-over-its-kzn-business-following-riots-25adb87b-ea37-41e7-9f84-e7c40b0781e5 [Accessed 10 August 2021].

[30] Dludla, Ngobile (2021), op. cit.

[31] SA News (2021) ‘Dtic Announces Economic Recovery Support Interventions’, 11 August, Available at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/dtic-announces-economic-recovery-support-interventions [Accessed 12 August 2021].

[32] The Presidency (2021) ‘Update by President Cyril Ramaphosa on Security Situation in the Country’, 16 July, Available at: http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/speeches/update-president-cyril-ramaphosa-security-situation-country [Accessed 10 August 2021].

[33] Ibid.

[34] Oxfam South Africa (2020) ‘Reclaiming Power: Women’s Work and Income Inequality in South Africa November 2020’, p. 12, Available at: https://www.oxfam.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/oxfam-sa-inequality-in-south-africa-report-2020.pdf [Accessed 2 August 2021].

[35] United Nations Human Development Report (2020) ‘South Africa, Human Development Indicators’, Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/ZAF [Accessed 3 August 2021].

[36] StatsSA (2021) ‘Youth Still Find it Difficult to Secure Jobs in South Africa’, 4 June, Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14415 [Accessed 11 August 2021].

[37] News24 (2021) ‘SA Lost Half a Million Formal-sector Jobs in a Year, New Data Show’, 29 June, Available at: https://www.news24.com/fin24/economy/south-africa/sa-lost-half-a-million-formal-sector-jobs-in-a-year-new-data-show-20210629 [Accessed 11 August 2021].

[38] South African Department of Health (2021) ‘Update on Covid-19 (Monday 25 October 2021)’, Covid-19 Online Resource and News Portal, 25 October, Available at: https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/10/24/update-on-covid-19-sunday-24-october-2021 [Accessed 24 October 2021].

[39] StatsSA (2021) ‘Covid-19 Epidemic Reduces Life Expectancy in 2021’, 19 July, Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14519 [Accessed 11 August 2021].

[40] StatsSA (2021) ‘GDP Rises in the First Quarter of 2021’, 8 June, Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14423 [Accessed 12 August 2021].

[41] Institute for Economics and Peace (2021) ‘Global Peace Index 2021: Measuring Peace in a Complex World’, Sydney, June, Available at: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GPI-2021-web-1.pdf [Accessed 12 August 2021].

[42] Magnus, Liela (2021) ‘Joburg Police Recover Firearms, Ammunition, Drugs and Looted Goods in Overnight Raids’, SABC News, 17 July, Available at: https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/joburg-police-recover-firearms-ammunition-drugs-and-looted-goods-in-overnight-raid[Accessed 12 August 2021].

[43] Cloke, Kenneth and Goldsmith, Joan (2011) Resolving Conflicts at Work: Eight Strategies for Everyone on the Job. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, p. xxxiv.